It is not uncommon to have interactive tree problems where you are allowed to query some connected component of the tree and use the return value to determine whether the answer is in the connected component or outside the connected component (Link to example problem). The general approach for these kinds of problems is to always choose a connected component of size $$$\frac{n}{2}$$$. However, there are also problems where the allowed queries are more restricted, preventing $$$\frac{n}{2}$$$ halving from being possible. This blog covers one of those types of problems.

Definitions

- Subtree: $$$S(r, u)$$$ contains the set of vertices in the subtree of vertex $$$u$$$ if the tree was rooted at vertex $$$r$$$.

- Neighbour: $$$N(u)$$$ contains the set of vertices that are directly adjacent to vertex $$$u$$$.

- Extended subtree: $$$ES(r, V) = \bigcup_{v\in V} S(r, v)\text{ if } v\in N(r)$$$. In other words, an extended subtree is a combination of the subtrees of a chosen set of vertices that are directly adjacent to the root.

Problem Structure

There is a hidden special vertex in a tree with $$$n$$$ vertices. Find the special vertex using at most $$$\lceil\log_{1.5}n\rceil$$$ of the following query:

- Choose an extended subtree of the tree. The grader will return whether the special vertex is in the chosen extended subtree. More formally, choose any vertex $$$r$$$ and a subset of neighbours $$$V \subseteq N(r)$$$, then the grader will return whether the special vertex $$$x \in ES(r, V)$$$.

Solution

Let us denote the size of the chosen extended subtree as $$$x$$$. If the grader returns that the special vertex is in the extended subtree, we can combine the root with the extended subtree to form a new tree with $$$x + 1$$$ vertices. Otherwise, the vertices outside of the extended subtree form a tree with $$$n - x$$$ vertices. This means that with each query, we can reduce the size of the tree to at least $$$\max(x + 1, n - x)$$$.

Since we are allowed to use $$$\lceil\log_{1.5}n\rceil$$$ queries, we will be able to solve this problem if the size of the tree reduces to at least $$$\frac{2n}{3}$$$ after each query. Solving the inequality $$$\max(x + 1, n - x) \le \frac{2n}{3}$$$, we get $$$\frac{n}{3} \le x \le \frac{2n}{3} - 1$$$. Now, let us see whether it is always possible to find an extended subtree of size between $$$\frac{n}{3}$$$ and $$$\frac{2n}{3} - 1$$$.

Let us root the tree at its centroid. Recall that all the children of the centroid have subtree sizes less than or equal to $$$\frac{n}{2}$$$. If there exists a child with subtree size more than or equal to $$$\frac{n}{3}$$$, then that lone subtree can be the chosen extended subtree since $$$\frac{n}{3} \le x \le \frac{n}{2} \le \frac{2n}{3} - 1$$$ $$$^\dagger$$$. From this point onwards, we will assume that all children of the centroid have subtree sizes less than $$$\frac{n}{3}$$$.

We will add the children of the centroid one by one into the extended subtree until the first time that the size of the extended subtree becomes more than or equal to $$$\frac{n}{3}$$$. Note that this is always possible as taking all children will result in a size of $$$n - 1$$$ which is more than or equal to $$$\frac{n}{3}$$$. Let $$$x$$$ be the size of the resultant extended subtree and let $$$p$$$ be the size of the last child that was added into the extended subtree. We can obtain the following inequalities: $$$x \ge \frac{n}{3}$$$, $$$x - p < \frac{n}{3}$$$, and $$$p < \frac{n}{3}$$$. Combining the second and third inequality, we obtain $$$x < \frac{2n}{3}$$$. Hence, $$$\frac{n}{3} \le x \le \frac{2n}{3} - 1$$$ and the desired extended subtree is found.

$$$^\dagger$$$ Note that $$$\frac{n}{2} \le \frac{2n}{3} - 1$$$ might not be true when $$$n \le 5$$$, however, this is not very important as $$$n - 1 \le \lceil \log_{1.5} n \rceil$$$ when $$$n \le 5$$$, so we can just query every subtree except for vertex 1 to get the answer.

Optimality

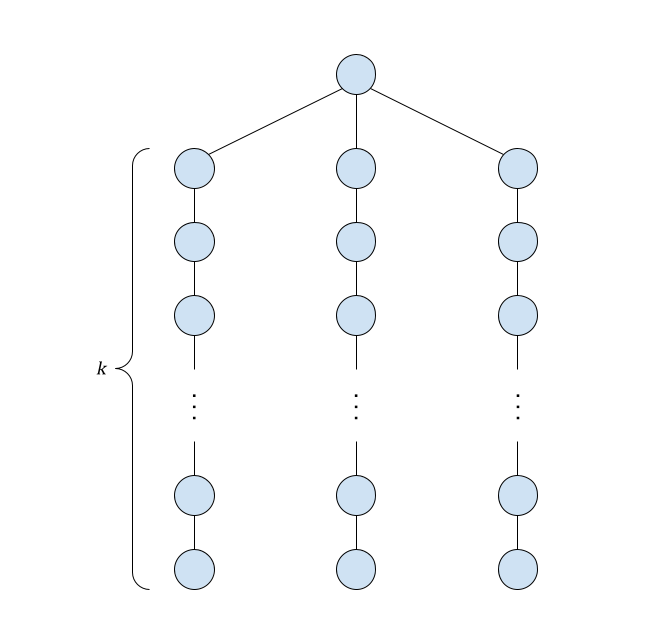

It might feel like $$$\lceil\log_{1.5}n\rceil$$$ is a loose bound and we can do better. However, we can prove that it is not possible to do any better. Special thanks to pavement and jamessngg for helping me to come up with this proof. Consider the tree below.

There are $$$n = 3k + 1$$$ vertices in the tree. The closest we can get to an extended subtree of size $$$\frac{n}{2}$$$ is either a single chain of size $$$k$$$ or two chains having size $$$2k$$$. Both of those options will result in a tree of size $$$2k + 1 \approx \frac{2n}{3}$$$ in the worst case after a query. This shows that for all $$$n = 3k + 1$$$, there exists a tree where it is not possible to reduce the size of the tree by less than $$$\frac{2n}{3}$$$ in a single query. We can use similar trees but with different chain lengths to come up with a similar proof for $$$n = 3k + 2$$$ and $$$n = 3k + 3$$$ to obtain the proof for all $$$n$$$.

An issue with this proof is that it does not account for amortisation. For the tree that was shown above, even though it is not possible to reduce the size of the tree by less than $$$\frac{2n}{3}$$$ in the first query, the next query will be done on a single chain of length $$$2k + 1$$$, which makes it easy for the remaining queries to reduce the size of the chain by half each time. Hence, this proof is not quite complete yet and I would appreciate it if anyone could tell me if they come up with a new idea.

Example

Abridged statement

You are given a tree consisting of $$$n$$$ nodes and there are two distinct nodes $$$a$$$ and $$$b$$$ that you have to determine. You can ask up to 40 queries of the form: $$$k\ \ x_1\ \ x_2\ \ldots\ x_k$$$ and the grader will return the distance between the lowest common ancestor of $$$x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k$$$ if the tree was rooted at $$$a$$$ and the lowest common ancestor of $$$x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k$$$ if the tree was rooted at $$$b$$$.

Solution

If we query all the vertices, we will be able to determine the distance between $$$a$$$ and $$$b$$$. Let this distance be $$$d$$$. Suppose we query an extended subtree together with its root. If the return value is $$$0$$$, it means that both $$$a$$$ and $$$b$$$ are outside of the extended subtree. If the return value is $$$d$$$, it means that both $$$a$$$ and $$$b$$$ are in the extended subtree or the root. Lastly, if the return value is between $$$1$$$ and $$$d - 1$$$, we know the distance that $$$a$$$ and $$$b$$$ are away from the root, so we can do two separate binary searches to find each of them.

Using the above-mentioned algorithm to choose the optimal extended subtree, we can solve this problem using $$$1 + \log_{1.5} n + 2\log_2 n \le 40$$$ queries. Note that there is a solution that uses only $$$2\log_2 n$$$ queries in the editorial of the problem, however, I feel like my solution is easier to come up with as it was the solution that I came up with during the contest.

Conclusion

I hope this will be interesting and useful to some people 🥺. Please let me know in the comments if you can come up with a better proof that handles the amortisation or maybe even come up with a more optimal algorithm that can perform better than $$$\log_{1.5} n$$$ queries by making use of the amortisation. If you are aware of other problems that can be solved using this technique, feel free to let me know in the comments as well. Thank you for your support 😁.

Nice blog, but I think there's a small mistake in this proof:

But $$$\frac{2n}{3}$$$ is not an integer, so $$$x < \frac{2n}{3}$$$ does not imply $$$x \le \frac{2n}{3}−1$$$. In fact, it's impossible to get $$$\frac{n}{3} \le x \le \frac{2n}{3}−1$$$ on the tree you give just below.

The only case where there does not exist an order in which to add the subtrees to satisfy the inequality is when $$$n = 3k + 1$$$ and we have $$$3$$$ children of size $$$k$$$.

We can notice that after the query we get either $$$n = k + 1$$$ or $$$n = 2k + 1$$$. In the first case, everything is ok. In the second case, in the next query we will get $$$n = k + 1$$$. In two queries, we want to have reduced the size of the tree by at least $$$\frac{4}{9}$$$ times, so $$$4(3k + 1) \ge 9(k + 1)$$$ must hold. Transforming the inequality, we get $$$k \ge \frac{5}{3}$$$, so $$$n \ge 6$$$. Since we handle the $$$n \le 5$$$ cases separately, this is enough to fix the proof, though we have to handle the $$$n = 5$$$ case such that we always reduce the size of the tree to at most $$$3$$$ vertices.

Note that "$$$3$$$ children of size $$$k$$$" is the only case in which it is impossible to make $$$x \le \frac{2n}{3} − 1$$$, but if we add subtrees in any order, the algorithm might also fail for a tree with $$$2$$$ children of size $$$k$$$. But then in the proof above, we can just merge the other children into one subtree of size $$$k$$$, since by taking some, but not all of them, we always get $$$x \le \frac{2n}{3} − 1$$$ (after the second query, we still get $$$n = k + 1$$$ because we choose the large child first).

The first question is the problem "search" from this EJOI isn't it?

What I did was everytime i "eliminate" one side of the tree if the root has two children, and then i find the centroid in the tree after i "cut off" one of the sides, then i query on that centroid

If its in it, you have reduced by 1/2 because you will eliminate one of the sides of its children and you will be left with one children which has at most n/2 nodes, if its not you have reduced by 1/2 because the rest of the tree is at most n/2.

This gives i think 2log2(n) queries which passed to 100 for me (I participated in the mirror)

Also i know this might be the same solution its just that the point of view here is different

he says the it is sufficient to do log2(n) operations in some problems , and that ejoi problem is one of them. His technique is good for different problems

I'm thinking of a case like this (perfect ternary tree), where it should have 1/3, 2/3 splits all the way down. But there is one doubt, which is certain decompositions have some edges upwards, which means it's not perfectly 1/3,2/3

So I tested this case (by doing knapsack-like DP on each node to get best split; then recursing on best split, and finding max depth of edge-centroid-decomp-tree 255249875)

so a perfect ternary tree with max depth

lhas1+3+3^2+...+3^l = (3^(l+1)-1)/2nodes. and the above code gave:So assuming this pattern is correct: (big assumption)

a tree with

n=(3^(l+1)-1)/2nodes has max edge-centroid-decomp-tree depth =2*l+1, whereaslog1.5((3^(l+1)-1)/2)has an oblique asymptote ofl*log1.5(3) + 1The oblique asymptote of

n=l*log1.5(3) + 1checks out because we can solve forl, then plug it into(3^(l+1)-1)/2:(3^((n-1)/log1.5(3)+1)-1)/2, and it equalslog1.5(n)exactlyDoing a similar thing but instead with

2*l+1, and noting 2 =log(3) / log(sqrt(3)), we get that max edge-centroid-decomp-tree depth in this case =log(n)/log(sqrt(3)) + log(2)/log(sqrt(3))=log(2n/sqrt(3)) / log(sqrt(3))basically showing amortized complexity is at least as bad as log with base = sqrt(3)