I like sorting algorithms very much, and I usually come up with weird ideas for sorting. Sometimes I wonder would those work properly, and now when I finally have the time from social distancing, I decided to start a series on my eccentric ideas — Weird sorts.

As an introductory problem for Dynamic Programming, you all probably know about the Longest Increasing Subsequence problem (LIS). But what if we apply this… to sorting? Today in the first blog of the Weird sorts series, I introduce to you… the LIS sort.

Basic idea

The core idea is to extract the LIS from the current array and repeat it until the current array is empty. It can be shown that this process always terminates, because there will always be a LIS that have a size of at least 1, thus at each pass, we will always take at least 1 element away from the array. In the implementation, we will first find the LIS of the array and separate the LIS from the rest of the array. We will then recursively perform the LIS sort on the remaining items, and merge them with the LIS using the same technique in Merge sort. The pseudocode looks something like this:

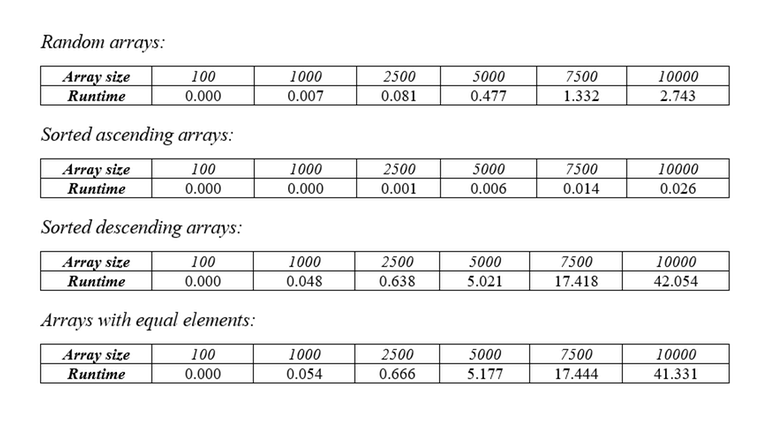

For better understanding, see this animation. The flaw of this algorithm lies in the number of passes that it must perform. In the worst case, the array will be in a non-decreasing order, requiring N passes to completely empty the array. Assuming you are using the standard way of finding LIS, each pass will cost $$$O(N^2)$$$, making the total complexity of this algorithm $$$O(N^3)$$$. Below are the tables of runtime with different types of arrays.

Optimization 1

The most time-consuming part of the sort is the step where we are looking for the LIS, which costs $$$O(N^2)$$$, so we should start optimizing from there. For optimizing the LIS problem from $$$O(N^2)$$$ to $$$O(N * \log{N})$$$, there have been many pages and articles written about this, so you should look them up for yourself. Here’s my favorite site: link.

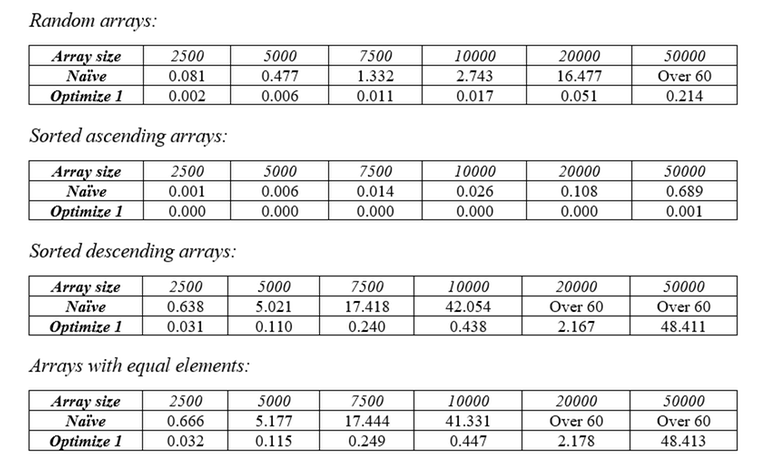

Other than that, the rest of the code is the same. By reducing the cost of finding LIS from $$$O(N^2)$$$ down to $$$O(N * \log{N})$$$, we have reduced the worst-case complexity of the sort from $$$O(N^3)$$$ to $$$O(N^2 * \log{N})$$$. Again, here are the tables of runtime with different types of arrays.

Optimization 2

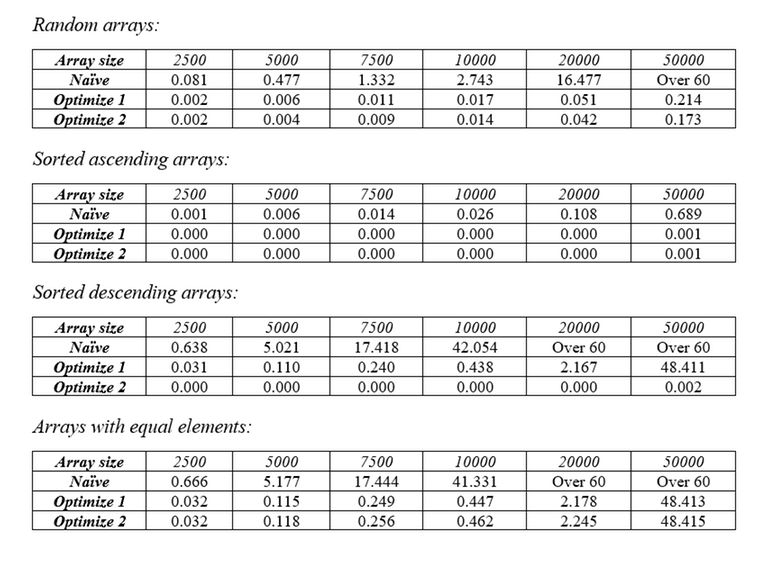

In the last 2 tests we can see that the sort performs exceptionally bad when it comes to descending arrays and arrays with equal elements. Also, when a LIS is taken from an array, there are high chances that the remaining items will form a non-increasing subsequence (this isn’t always the case, however). So, by reversing the remaining array, we increase the chance of more items being taken away from it in the next pass, thus improving the runtime of the average case and the case where the array is decreasing. Here are the tables of runtime with different types of arrays.

Optimization 3

You may realize that it still performs pretty bad in the case where the array contains equal elements. It’s easy to fix this, however: instead of finding the longest increasing subsequence, we will find the longest non-decreasing subsequence. This makes sure that all equal elements are covered in one pass. Surprisingly, this even lowers the upper bound of the number of passes the sort needs to do.

How? Well first, let’s call the number of increasing subsequences is $$$A$$$ and length of the shortest one is $$$B$$$. Because the array is reversed on each pass, so either the longest increasing subsequence or an element of every other increasing subsequence is taken. Therefore, the last subsequence we take will be the shortest one (providing we didn’t take all of its elements before), so the number of passes should be $$$\min(A,B)$$$.

Now we will try to generate an array that maximizes $$$\min(A,B)$$$, which is basically the worst case. First, let’s fix the value of $$$A$$$ and maximize $$$B$$$ based on $$$A$$$. We have:

In the above equation, $$$L_i$$$ denotes for the length of the $$$i_{th}$$$ increasing subsequence. For some $$$k$$$, let $$$L_k$$$ be the length of the shortest increasing subsequence. We will have:

ㅤ

So, when B is maximized, $$$N=A*B$$$. From the equation we just deducted, we can show that the upper bound of $$$\min(A,B)$$$ is $$$\sqrt{N}$$$. To prove it, let’s assume that $$$\min(A,B)>\sqrt{N}$$$.

ㅤ

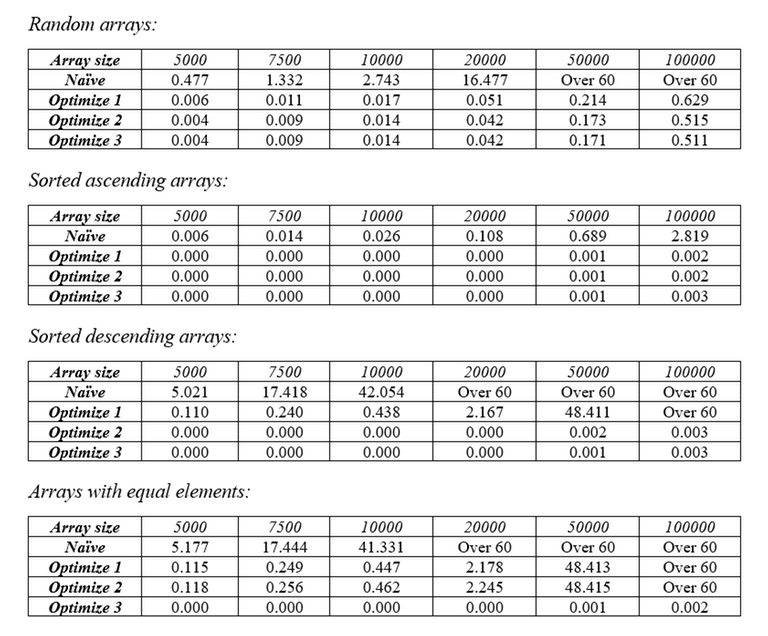

Hence, in the worst case, $$$min(A,B) = \sqrt{N}$$$. Since we need 1 pass to take the longest subsequence and 1 extra pass to take the first element of every other subsequence, the number of passes will never exceed $$$2\sqrt{N}$$$. So, the time complexity of this sorting algorithm is $$$O(N\sqrt{N} * \log{N})$$$. Of course, that’s just all the theory, let’s see how this optimization actually performs in benchmarks. Here are the tables of runtime with different types of arrays.

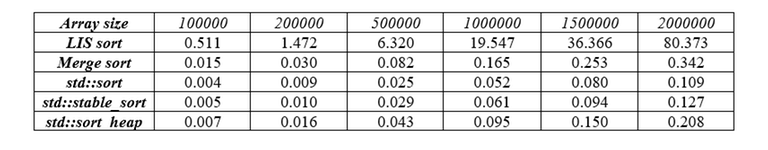

Since it performs pretty good even in edge cases, let’s put it against the real pros on the battle. Here’s the table of runtime with the LIS sort and various other sorts on random arrays.

While it was much faster than its unoptimized variants, it’s having a hard time trying to keep up with other sorts. This is due to the extra $$$O(\sqrt{N})$$$ cost of processing different passes, compared to other sorts that perform only in $$$O(N * \log{N})$$$.

Technical details

All tests in this blog are benchmarked with an i7-1165G7 running at 3.30 GHz with 16 GB of RAM. All numbers were randomly and uniformly generated in the range $$$[1, 10^6]$$$ using the testlib.h library (source). Execution time was measured in seconds. The codes were executed on CodeBlocks 20.03 using C++14 and Release build target. Tests were repeated 20 times and the final value was taken from the average of 20 values.

Here are all the source codes I used to benchmark: link

Summary

To be honest, I don’t think there are any practical uses of this sort. There are many other sorting algorithms that are both faster, and more memory efficient. However, I did learn a lot while doing research and looking for proofs, especially about inequalities.

Special thanks to CatnipIsAddictive and horigin who helped me with the proofs, and to my friends who proofread this blog. Also this is the first time I write such a long blog, so mistakes are inevitable. Please comment about logical errors or grammar mistakes if you find any, or just share your thought. Thank you all for reading my little blog.

or2

Interesting blog, really.

But you still hadn't prooved that there is no test that runs slower that $$$O(n \sqrt{n} \log(n))$$$.

If $$$N \geq A \cdot B$$$, you cannot say that "if you maximize B then $$$N = A \cdot B$$$", that's not mathematically correct.

So the question is still opened: is there a counter-example for your $$$O(n \sqrt{n} \log(n))$$$ solution? Or is there a complete proof?

Well originally I wrote it like this: If $$$N \geq A * B$$$ then $$$\frac{N}{A} \geq B$$$, so $$$B$$$ is maximized when $$$B = \frac{N}{A} \Rightarrow N = A * B$$$.

It seems very intuitive for me, but of course there might be something wrong in my logic.

OK. For example, if $$$A = n$$$ and $$$B = 1$$$, your algorithm needs $$$O(n^2 \log(n))$$$ operations. Can you proove that there is no such test?

Or, for example, $$$A = \frac{n}{\log(n)}$$$, $$$B = \log(n)$$$. There $$$A \cdot B = n$$$, and your algo runs in $$$O(n^2)$$$.

Hmm, this is an interesting case. Thanks for pointing out, as a newbie it helps me a lot. I'll do some testing to see if there are such any tests like that.

It is an instance of Dilworth's theorem that the minimum number of non-decreasing subsequences into which a given finite sequence can be partitioned is equal to the length of the longest strictly decreasing subsequence. So, the length of the longest non-decreasing subsequence times the length of the longest non-increasing subsequence is at least $$$n$$$. So, their sum is at least $$$2 \cdot \sqrt{n}$$$ and thus the first two passes must remove a total of at least $$$2 \cdot \sqrt{n} - 1$$$ elements. Finally, since $$$\sqrt{n} - \sqrt{n - 2 \cdot \sqrt{n} + 1} = 1$$$, this implies that the number of passes is at most $$$2 \cdot \sqrt{n}$$$.

Wow, beatiful. Thanks!

You can proof it with pigeonhole principle that the complexity of a worst case is $$$O(n\sqrt{n}\log(n))$$$.

Lets define a sequence $$$A$$$ of $$$N$$$ integers such that $$$A_i$$$ is distinct for each $$$i$$$ from 1 to $$$N$$$. Lets define a pair $$$i,j$$$ such that $$$i<j$$$. Lets define a sequence $$$X$$$ and $$$Y$$$ of length $$$N$$$ such that $$$X_i$$$ is equal to the Longest increasing Subsequence from $$$1$$$ to $$$i$$$ and $$$Y_i$$$ is equal to Longest Decreasing Subsequence from $$$i$$$ to $$$N$$$ If $$$A_i<A_j$$$, then $$$X_j>X_i$$$ otherwise, if $$$A_i>A_j$$$, then $$$Y_i>Y_j$$$. Notice that the case of $$$X_i=Y_i$$$ and $$$Y_i=Y_j$$$ would never occur due to the fact that either $$$A_i>A_j$$$ will happen or $$$A_i<A_j$$$ will happen(mutually exclusive). So, assuming that $$$X_i$$$ and $$$Y_i$$$ are less than $$$\left \lceil{\sqrt{N}}\right \rceil $$$, by pigeonhole principle, it is impossible for that sequence to exist. Thus, it is proved that the complexity of the algorithm is $$$O(n\sqrt{n}\log(n))$$$.

Where is pigeon hole used?

When going from i to i+1, either Xi or Yi changes. So the number of distinct (Xi,Yi) pairs >= N.

Now assuming Xi,Yi < sqrt(N), there are < sqrt(N) distinct choices for Xi,Yi. So < sqrt(N)*sqrt(N) choices for a (Xi,Yi) pair (contradiction)

Wow I didn't expect there would be that much people interested in my blog, especially Masters. Thank you very much!

In optimization 2, do you reverse the remaining array in each pass or just after the first 1?

I reverse the array on each pass. You can study more in my implementation!

OK Thanks! Also, nice blog! Really learnt a lot about inequalities.