This blog assumes the reader is familiar with the basic concept of rolling hashes. There are some math-heavy parts, but one can get most of the ideas without understanding every detail.

The main focus of this blog is on how to choose the rolling-hash parameters to avoid getting hacked and on how to hack codes with poorly chosen parameters.

Designing hard-to-hack rolling hashes

Recap on rolling hashes and collisions

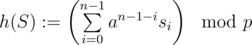

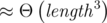

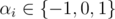

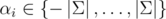

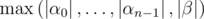

Recall that a rolling hash has two parameters (p, a) where p is the modulo and 0 ≤ a < p the base. (We'll see that p should be a big prime and a larger than the size  of the alphabet.) The hash value of a string S = s0... sn - 1 is given by

of the alphabet.) The hash value of a string S = s0... sn - 1 is given by

For now, lets consider the simple problem of: given two strings S, T of equal length, decide whether they're equal by comparing their hash values h(S), h(T). Our algorithm declares S and T to be equal iff h(S) = h(T). Most rolling hash solutions are built on multiple calls to this subproblem or rely on the correctness of such calls.

Let's call two strings S, T of equal length with S ≠ T and h(S) = h(T) an equal-length collision. We want to avoid equal-length collisions, as they cause our algorithm to incorrectly assesses S and T as equal. (Note that our algorithms never incorrectly assesses strings a different.) For fixed parameters and reasonably small length, there are many more strings than possible hash values, so there always are equal-length collisions. Hence you might think that, for any rolling hash, there are inputs for which it is guaranteed to fail.

Luckily, randomization comes to the rescue. Our algorithm does not have to fix (p, a), it can randomly pick then according to some scheme instead. A scheme is reliable if we can prove that for arbitrary two string S, T, S ≠ T the scheme picks (p, a) such that h(S) ≠ h(T) with high probability. Note that the probability space only includes the random choices done inside the scheme; the input (S, T) is arbitrary, fixed and not necessarily random. (If you think of the input coming from a hack, then this means that no matter what the input is, our solution will not fail with high probability.)

I'll show you two reliable schemes. (Note that just because a scheme is reliable does not mean that your implementation is good. Some care has to be taken with the random number generator that is used.)

Randomizing base

This part is based on a blog by rng_58. His post covers a more general hashing problem and is worth checking out.

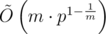

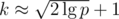

This scheme uses a fixed prime p (i.e. 109 + 7 or 4·109 + 7) and picks a uniformly at random from  . Let A be a random variable for the choice of a.

. Let A be a random variable for the choice of a.

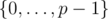

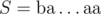

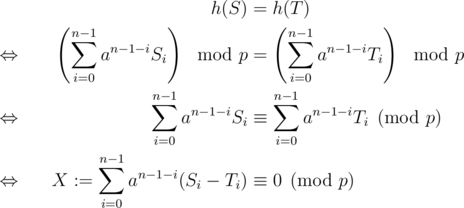

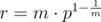

To prove that this scheme is good, consider two strings (S, T) of equal length and do some calculations

Note that the left-hand side, let's call it P(A), is a polynomial of degree ≤ n - 1 in A. P is non-zero as S ≠ T. The calculations show that h(S) = h(T) if and only if A is a root of P(A).

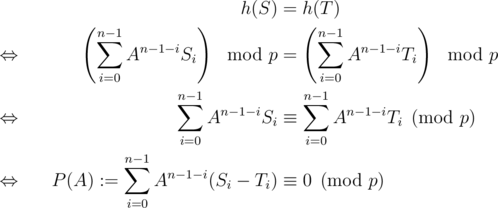

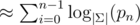

As p is prime and we are doing computations  , we are working in a field. Over a field, any polynomial of degree ≤ n - 1 has at most n - 1 roots. Hence there are at most n - 1 choices of a that lead to h(S) = h(T). Therefore

, we are working in a field. Over a field, any polynomial of degree ≤ n - 1 has at most n - 1 roots. Hence there are at most n - 1 choices of a that lead to h(S) = h(T). Therefore

So for any two strings (S, T) of equal length, the probability that they form an equal-length collision is at most  . This is around 10 - 4 for n = 105, p = 109 + 7. Picking larger primes such as 231 - 1 or 4·109 + 7 can improve this a bit, but one needs more care with overflows.

. This is around 10 - 4 for n = 105, p = 109 + 7. Picking larger primes such as 231 - 1 or 4·109 + 7 can improve this a bit, but one needs more care with overflows.

Tightness of bound

For now, this part only applies to primes with smooth p - 1, so it doesn't work for p = 109 + 7 for example. It would be interesting to find a construction that is computable and works in the general case.

The bound  for this scheme is actually tight if

for this scheme is actually tight if  . Consider

. Consider  and

and  with

with

As p is prime,  is cyclic of order p - 1, hence there is a subgroup

is cyclic of order p - 1, hence there is a subgroup  of order n - 1. Any

of order n - 1. Any  then satisfies gn - 1 = 1, so P(A) has n - 1 distinct roots.

then satisfies gn - 1 = 1, so P(A) has n - 1 distinct roots.

Randomizing modulo

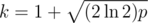

This scheme fixes a base  and a bound N > a and picks a prime p uniformly at random from [N, 2N - 1].

and a bound N > a and picks a prime p uniformly at random from [N, 2N - 1].

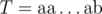

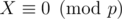

To prove that this scheme is good, again, consider two strings (S, T) of equal length and do some calculations

As  ,

,  . As we chose a large enough, X ≠ 0. Moreover

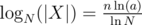

. As we chose a large enough, X ≠ 0. Moreover  . An upper bound for the number of distinct prime divisors of X in [N, 2N - 1] is given by

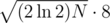

. An upper bound for the number of distinct prime divisors of X in [N, 2N - 1] is given by  . By the prime density theorem, there are around

. By the prime density theorem, there are around  primes in [N, 2N - 1]. Therefore

primes in [N, 2N - 1]. Therefore

Note that this bound is slightly worse than the one for randomizing the base. It is around 3·10 - 4 for n = 105, a = 26, N = 109.

How to randomize properly

The following are good ways of initializing your random number generator.

- high precision time.

chrono::duration_cast<chrono::nanoseconds>(chrono::high_resolution_clock::now().time_since_epoch()).count();

chrono::duration_cast<chrono::nanoseconds>(chrono::steady_clock::now().time_since_epoch()).count();

Either of the two should be fine. (In theory, high_resolution_clock should be better, but it somehow has lower precision than steady_clock on codeforces??)

- processor cycle counter

__builtin_ia32_rdtsc();

- some heap address converted to an integer

(uintptr_t) make_unique<char>().get();

- processor randomness (needs either pragma or asm) (Thanks halyavin for suggesting this.)

// pragma version

#pragma GCC target ("rdrnd")

uint32_t rdrand32(){

uint32_t ret;

assert(__builtin_ia32_rdrand32_step (&ret));

return ret;

}

// asm version

uint32_t rd() {

uint32_t ret;

asm volatile("rdrand %0" :"=a"(ret) ::"cc");

return ret;

}

If you use a C++11-style rng (you should), you can use a combination of the above

seed_seq seq{

(uint64_t) chrono::duration_cast<chrono::nanoseconds>(chrono::high_resolution_clock::now().time_since_epoch()).count(),

(uint64_t) __builtin_ia32_rdtsc(),

(uint64_t) (uintptr_t) make_unique<char>().get()

};

mt19937 rng(seq);

int base = uniform_int_distribution<int>(0, p-1)(rng);

Note that this does internally discard the upper 32 bits from the arguments and that this doesn't really matter, as the lower bits are harder to predict (especially in the first case with chrono.).

See the section on 'Abusing bad randomization' for some bad examples.

Extension to multiple hashes

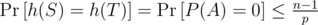

We can use multiple hashes (Even with the same scheme and same fixed parameters) and the hashes are independent so long as the random samples are independent. If the single hashes each fail with probability at most α1, ..., αk, the probability that all hashes fail is at most  .

.

For example, if we use two hashes with p = 109 + 7 and randomized base, the probability of a collision is at most 10 - 8; for four hashes it is at most 10 - 16. Here the constants from slightly larger primes are more significant, for p = 231 - 1 the probabilities are around 2.1·10 - 9 and 4.7·10 - 18.

Larger modulo

Using larger (i.e. 60 bit) primes would make collision less likely and not suffer from the accumulated factors of n in the error bounds. However, the computation of the rolling hash gets slower and more difficult, as there is no __int128 on codeforces.

One exception to this is the Mersenne prime p = 261 - 1; we can reduce  by using bitshifts instead. (Thanks dmkozyrev for suggesting this.) The following code computes

by using bitshifts instead. (Thanks dmkozyrev for suggesting this.) The following code computes  without

without __int128 and is only around 5 % slower than a 30 bit hash with modulo.

A smaller factor can be gained by using unsigned types and p = 4·109 + 7.

Note that p = 264 (overflow of unsigned long long) is not prime and can be hacked regardless of randomization (see below).

Extension to multiple comparisons

Usually, rolling hashes are used in more than a single comparison. If we rely on m comparison and the probability that a single comparison fails is p then the probability that any of the fail is at most m·p by a union bound. Note that when m = 105, we need at least two or three hashes for this to be small.

One has to be quite careful when estimating the number comparison we need to succeed. If we sort the hashes or put them into a set, we need to have pair-wise distinct hashes, so for n string a total of  comparisons have to succeed. If n = 3·105, m ≈ 4.5·109, so we need three or four hashes (or only two if we use p = 261 - 1).

comparisons have to succeed. If n = 3·105, m ≈ 4.5·109, so we need three or four hashes (or only two if we use p = 261 - 1).

Extension to strings of different length

If we deal with strings of different length, we can avoid comparing them by storing the length along the hash. This is not necessarily however, if we assume that no character hashes to 0. In that case, we can simple imagine we prepend the shorter strings with null-bytes to get strings of equal length without changing the hash values. Then the theory above applies just fine. (If some character (i.e. 'a') hashes to 0, we might produce strings that look the same but aren't the same in the prepending process (i.e. 'a' and 'aa').)

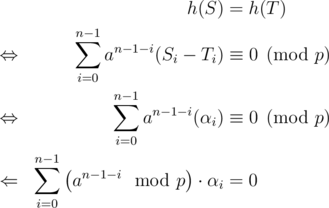

Computing anti-hash tests

This section cover some technique that take advantage of common mistakes in rolling hash implementations and can mainly be used for hacking other solutions. Here's a table with a short summary of the methods.

| Name | Use case | Runtime | String length | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thue-Morse | Hash with overflow | Θ(1) | 210 | Works for all bases simultaneously. |

| Birthday | Small modulo |  |  | Can find multiple collisions. |

| Tree | Large modulo |  |  | faster; longer strings |

| Multi-tree | Large modulo |  |  | slower; shorter strings |

| Lattice reduction | Medium-large alphabet, Multiple hashes |  |  | Great results for  , good against multiple hashes. Bad on binary alphabet. , good against multiple hashes. Bad on binary alphabet. |

| Composition | Multiple hashes | Sum of single runtimes | Product of single string lengths | Combines two attacks. |

Single hashes

Thue–Morse sequence: Hashing with unsigned overflow (p = 264, q arbitrary)

One anti-hash test that works for any base is the Thue–Morse sequence, generated by the following code.

See this blog for a detailed discussion. Note that the bound on the linked blog can be improved slightly, as X2 - 1 is always divisible by 8 for odd X. (So we can use Q = 10 instead of Q = 11.)

Birthday-attack: Hashing with 32-bit prime and fixed base (p < 232 fixed, q fixed)

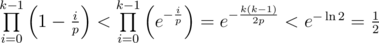

Hashes with a single small prime can be attacked via the birthday paradox. Fix a length l, let  and pick k strings of length l uniformly at random. If l is not to small, the resulting hash values will approximately be uniformly distributed. By the birthday paradox, the probability that all of our picked strings hash to different values is

and pick k strings of length l uniformly at random. If l is not to small, the resulting hash values will approximately be uniformly distributed. By the birthday paradox, the probability that all of our picked strings hash to different values is

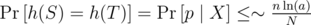

Hence with probability  we found two strings hashing to the same value. By repeating this, we can find an equal-length collision with high probability in

we found two strings hashing to the same value. By repeating this, we can find an equal-length collision with high probability in  . In practice, the resulting strings can be quite small (length ≈ 6 for p = 109 + 7, not sure how to upper-bound this.).

. In practice, the resulting strings can be quite small (length ≈ 6 for p = 109 + 7, not sure how to upper-bound this.).

More generally, we can compute m strings with equal hash value in  using the same technique with

using the same technique with  .

.

Tree-attack: Hashing with larger prime and fixed base (p fixed, q fixed)

Thanks Kaban-5 and --Pavel-- for the link to some Russian comments describing this idea.

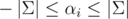

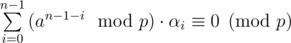

For large primes, the birthday-attack is to slow. Recall that for two strings (S, T) of equal length

where αi = Si - Ti satisfies  . The tree-attack tries to find

. The tree-attack tries to find  such that

such that

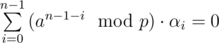

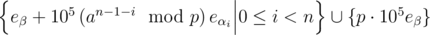

The attack maintains clusters C1, ..., Ck of coefficients. The sum S(C) of a cluster C is given by

We can merge two clusters C1 and C2 to a cluster C3 of sum S(C1) - S(C2) by multiplying all the αi from C2 with - 1 and joining the set of coefficients of C1 and C2. This operation can be implemented in constant time by storing the clusters as binary trees where each node stores its sum; the merge operation then adds a new node for C3 with children C1 and C2 and sum S(C1) - S(C2). To ensure that the S(C3) ≥ 0, swap C1 and C2 if necessary. The values of the αi are not explicitly stored, but they can be recomputed in the end by traversing the tree.

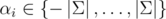

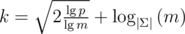

Initially, we start with n = 2k and each αi = 1 in its own cluster. In a phase, we first sort the clusters by their sum and then merge adjacent pairs of clusters. If we encounter a cluster of sum 0 at any point, we finish by setting all αj not in that cluster to 0. If we haven't finished after k phases, try again with a bigger value of k.

For which values of k can we expect this to work? If we assume that the sums are initially uniformly distributed in  , the maximum sum should decrease by a factor

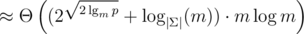

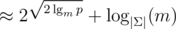

, the maximum sum should decrease by a factor  in phase i. After k phases, the maximum sum is around

in phase i. After k phases, the maximum sum is around  , so

, so  works. This produces strings of length

works. This produces strings of length  in

in  time. (A more formal analysis can be found in the paper 'Solving Medium-Density Subset Sum Problems in Expected Polynomial Time', section 2.2. The problem and algorithms in the paper are slightly different, but the approach similar.)

time. (A more formal analysis can be found in the paper 'Solving Medium-Density Subset Sum Problems in Expected Polynomial Time', section 2.2. The problem and algorithms in the paper are slightly different, but the approach similar.)

Multi-tree-attack

While the tree-attacks runs really fast, the resulting strings can get a little long. (n = 2048 for p = 261 - 1.) We can spend more runtime to search for a shorter collision by storing the smallest m sums we can get in each cluster. (The single-tree-attack just uses m = 1.) Merging two clusters can be done in  with a min-heap and a 2m-pointer walk. In order to get to m strings ASAP, we allow all values

with a min-heap and a 2m-pointer walk. In order to get to m strings ASAP, we allow all values  and exclude the trivial case where all αi are zero.

and exclude the trivial case where all αi are zero.

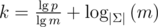

Analysing the expected value of k for this to work is quite difficult. Under the optimistic assumption that we reach m sums per node after  steps, that the sums decrease as in the single tree attack and that we can expected a collision when they get smaller than m2 by the birthday-paradox, we get

steps, that the sums decrease as in the single tree attack and that we can expected a collision when they get smaller than m2 by the birthday-paradox, we get  . (A more realistic bound would be

. (A more realistic bound would be  , which might be gotten by accounting for the birthday-paradox in the bound proven in the paper 'On Random High Density Subset Sums', Theorem 3.1.)

, which might be gotten by accounting for the birthday-paradox in the bound proven in the paper 'On Random High Density Subset Sums', Theorem 3.1.)

In practice, we can use m ≈ 105 to find a collision of length 128 for  , p = 261 - 1 in around 0.4 seconds.

, p = 261 - 1 in around 0.4 seconds.

Lattice-reduction attack: Single or multiple hashes over not-to-small alphabet

Thanks to hellman_ for mentioning this, check out his write-ups on this topic here and here.

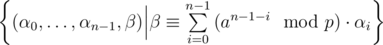

As in the tree attack, we're looking for  such that

such that

The set

forms a lattice (A free  -module embedded in a subspace of

-module embedded in a subspace of  .) We're looking for an element in the lattice such that β = 0 and

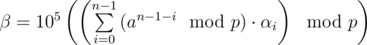

.) We're looking for an element in the lattice such that β = 0 and  . We can penalize non-zero values of β by considering

. We can penalize non-zero values of β by considering

instead, then we seek to minimize  . Unfortunately, this optimization problem is quite hard, so we try to minimize

. Unfortunately, this optimization problem is quite hard, so we try to minimize

instead. The resulting problem is still hard, possibly NP-complete, but there are some good approximation algorithms available.

Similar to a vector space, we can define a basis in a lattice. For our case, a basis is given by

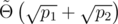

A lattice reduction algorithm takes this basis and transforms it (by invertible matrices with determinant ± 1) into another basis with approximately shortest vectors. Implementing them is quite hard (and suffers from precision errors or bignum slowdown), so I decided to use the builtin implementation in sage.

Sage offers two algorithms: LLL and BKP, the former is faster but produces worse approximations, especially for longer strings. Analyzing them is difficult, so I experimented a bit by fixing  , p = 261 - 1 and fixing a1, ..., an randomly and searching for a short anti-hash test with both algorithms. The results turned out really well.

, p = 261 - 1 and fixing a1, ..., an randomly and searching for a short anti-hash test with both algorithms. The results turned out really well.

Note that this attack does not work well for small (i.e binary) alphabets when n > 1 and that the characters have to hash to consecutive values, so this has to be the first attack if used in a composition attack.

Composition-attack: Multiple hashes

Credit for this part goes to ifsmirnov, I found this technique in his jngen library.

Using two or more hashes is usually sufficient to protect from a direct birthday-attack. For two primes, there are N = p1·p2 possible hash values. The birthday-attack runs in  , which is ≈ 1010 for primes around 109. Moreover, the memory usage is more than

, which is ≈ 1010 for primes around 109. Moreover, the memory usage is more than  bytes (If you only store the hashes and the rng-seed), which is around 9.5 GB.

bytes (If you only store the hashes and the rng-seed), which is around 9.5 GB.

The key idea used to break multiple hashes is to break them one-by-one.

- First find an equal-length collision (by birthday-attack) for the first hash h1, i.e. two strings S, T, S ≠ T of equal length with h1(S) = h1(T). Note that strings of equal length built over the alphabet S, T (i.e. by concatenation of some copies of S with some copies of T and vice-versa) will now hash to the same value under h1.

- Then use S and T as the alphabet when searching for an equal-length collision (by birthday-attack again) for the second hash h2. The result will automatically be a collision for h1 as well, as we used S, T as the alphabet.

This reduces the runtime  . Note that this also works for combinations of a 30-bit prime hash and a hash mod 264 if we use the Thue–Morse sequence in place of the second birthday attack. Similarly, we can use tree- instead of birthday-attacks for larger modulos.

. Note that this also works for combinations of a 30-bit prime hash and a hash mod 264 if we use the Thue–Morse sequence in place of the second birthday attack. Similarly, we can use tree- instead of birthday-attacks for larger modulos.

Another thing to note is that string length grows rapidly in the number of hashes. (Around  , the alphabet size is reduced to 2 after the first birthday-attack. The first iteration has a factor of 2 in practice.) If we search for more than 2 strings with equal hash value in the intermediate steps, the alphabet size will be bigger, leading to shorter strings, but the runtime of the birthday-attacks gets slower (

, the alphabet size is reduced to 2 after the first birthday-attack. The first iteration has a factor of 2 in practice.) If we search for more than 2 strings with equal hash value in the intermediate steps, the alphabet size will be bigger, leading to shorter strings, but the runtime of the birthday-attacks gets slower ( for 3 strings, for example.).

for 3 strings, for example.).

Abusing bad randomization

On codeforces, quite a lot of people randomize their hashes. (Un-)Fortunately, many of them do it an a suboptimal way. This section covers some of the ways people screw up their hash randomizations and ways to hack their code.

This section applies more generally to any type of randomized algorithm in an environment where other participants can hack your solutions.

Fixed seed

If the seed of the rng is fixed, it always produces the same sequence of random numbers. You can just run the code to see which numbers get randomly generated and then find an anti-hash test for those numbers.

Picking from a small pool of bases (rand() % 100)

Note that rand() % 100 produced at most 100 distinct values (0, ..., 99). We can just find a separate anti-hash test for every one of them and then combine the tests into a single one. (The way your combine tests is problem-specific, but it works for most of the problems.)

More issues with rand()

On codeforces, rand() produces only 15-bit values, so at most 215 different values. While it may take a while to run 215 birthday-attacks (estimated 111 minutes for p = 109 + 7 using a single thread on my laptop), this can cause some big issues with some other randomized algorithms.

Edit: This type of hack might be feasible if we use multi-tree-attacks. For  , running 215 multi-tree attacks with m = 104 takes around 2 minutes and produces an output of 5.2·105 characters. This is still slightly to large for most problems, but could be split up into multiple hacks in an open hacking phase, for example.

, running 215 multi-tree attacks with m = 104 takes around 2 minutes and produces an output of 5.2·105 characters. This is still slightly to large for most problems, but could be split up into multiple hacks in an open hacking phase, for example.

In C++11 you can use mt19937 and uniform_int_distribution instead of rand().

Low-precision time (Time(NULL))

Time(NULL) only changes once per second. This can be exploited as follows

- Pick a timespan Δ T.

- Find an upper bound T for the time you'll need to generate your tests.

- Figure out the current value T0 of

Time(NULL)via custom invocation. - For t = 0, ..., (Δ T) - 1, replace

Time(NULL)with T0 + T + t and generate an anti-test for this fixed seed. - Submit the hack at time T0 + T.

If your hack gets executed within the next Δ T seconds, Time(NULL) will be a value for which you generated an anti-test, so the solution will fail.

Random device on MinGW (std::random_device)

Note that on codeforces specifically, std::random_device is deterministic and will produce the same sequence of numbers. Solutions using it can be hacked just like fixed seed solutions.

Notes

- If I made a mistake or a typo in a calculation, or something is unclear, please comment.

- If you have your own hash randomization scheme, way of seeding the rng or anti-hash algorithm that you want to discuss, feel free to comment on it below.

- I was inspired to write this blog after the open hacking phase of round #494 (problem F). During (and after) the hacking phase I figured out how to hack many solution that I didn't know how to hack beforehand. I (un-)fortunately had to go to bed a few hours in (my timezone is UTC + 2), so quite a few hackable solutions passed.

should hold. The return value then also satisfies this.

should hold. The return value then also satisfies this.