Hello, Codeforces!

I recently came across a data structure that I find quite interesting: the sparse set. It functions similarly to a bitset and supports all its operations but has some quirks and useful features of its own. Particularly, unlike almost every other data structure, it does not need to be initialised at all before it can be used! Naturally, that also means that its data can be reset in $$$O(1)$$$ time, as opposed to the $$$O(n)$$$ time expected of regular bitsets. It also has the added benefit that traversing its elements takes time proportional to the number of elements rather than the size of the data structure, making the operation more efficient for sparse bitsets. However, note that it is likely less efficient in terms of its memory usage (still $$$O(n)$$$ but ~64× larger constant) and constant time factor.

Introduction

The sparse set consists simply of two integer arrays (which I'll call $$$d$$$ and $$$s$$$) and a size variable $$$n$$$, satisfying the following class invariants:

- Invariant 1: $$$d[0..(n-1)]$$$ (inclusive) stores the elements of the bitset;

- Invariant 2: If $$$e$$$ is an element of the bitset, then $$$s[e]$$$ stores its index in the $$$d$$$ array.

In most literature covering this data structure, the arrays $$$d$$$ and $$$s$$$ are called the 'dense' and the 'sparse' arrays, respectively.

For any array element not mentioned above, its value can be anything without affecting the function of the data structure.

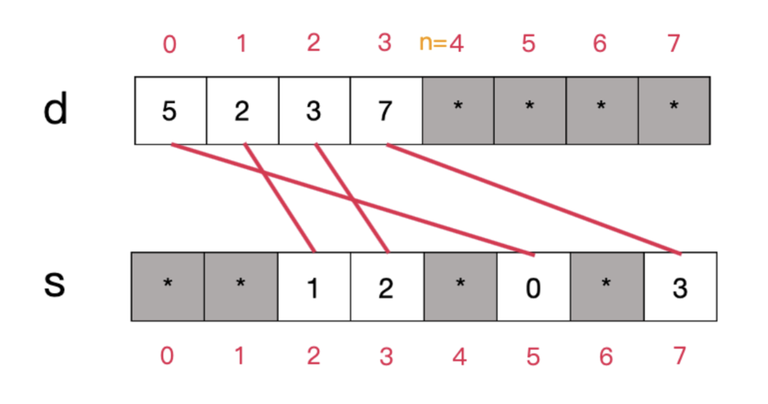

A typical sparse set might look like this (asterisk denotes terms that can be anything):

The red lines indicate the connections between the elements in $$$d$$$ and $$$s$$$. It can be shown that, for all indices $$$i$$$ in the range $$$[0, n-1]$$$, the constraint $$$d[s[d[i]]] = d[i]$$$ is satisfied.

In C++ code, the data structure can be represented as follows:

template <int N>

struct sparse_set {

int n;

int d[N], s[N];

};

Note that, in this article, we would use $$$N$$$ to denote the size of the data structure itself (and thus, the set of elements allowed is $$${0, 1, \ldots, N-1}$$$), and $$$n$$$ to denote the number of elements currently stored.

Important implementation detail: if you are using C, C++, or Rust, you still have to initialise this data structure in its constructor since accessing an uninitialised element does not return an unspecified value; it is undefined behaviour and can introduce bugs elsewhere in your program. You don't have to do this when resetting the data structure, however.